Embracing the Unpredictable: A Journey into Randomness and Random Numbers

Introduction

Randomness is everywhere. From the way leaves scatter on the sidewalk to the unpredictable interaction of subatomic particles, randomness shapes our world. But what exactly is randomness? And how do we, as humans and computer users, make sense of it? In this post, we explore the concept of randomness, its role in nature and science, and how computers attempt to simulate the unpredictable.

What is Randomness?

At its core, randomness refers to the absence of pattern or predictability. An event is random if it cannot be precisely determined in advance, even when the underlying process is understood. While this may sound abstract, randomness is central to mathematics, physics, computer science, and even philosophy

Randomness in the Natural World

Nature offers some of the most compelling examples of randomness:

- Radioactive Decay: Atoms decay at unpredictable moments, a cornerstone of quantum mechanics. The weak nuclear forces is the primary driver of radioactive decay.

- Genetic Mutations: Random errors during DNA replication drive evolution and biodiversity

- Weather: The butterfly effect demonstrates how small random variations can lead to drastically different weather

- Brownian Motion: Tiny particles in a fluid move erratically due to molecular collisions

- Tree Growth and Leaf Patterns: Branching structures and leaf shapes are partly the result of random developmental fluctuations

- Cosmic Rays: High-energy particles strike the Earth unpredictably, sometimes causing glitches in electronics

- Animal Movement: Creatures often use random strategies to search for food efficiently

Einstein and the Philosophy of Randomness

One of the most famous critiques of randomness came from Albert Einstein, who said:

“God does not play dice with the universe.“

Albert Einstein

Einstein was expressing his discomfort with the indeterminism of quantum mechanics. He believed that the apparent randomness of subatomic particles was due to some deeper, undiscovered laws. This statement sparked famous debates with physicist Niels Bohr, who reportedly replied:

“Stop telling God what to do.”

Niels Bohr

This exchange highlights a deep philosophical divide over whether randomness is a fundamental feature of reality. Einstein believed that the apparent randomness of quantum mechanics was a sign of an incomplete theory — a placeholder for a deeper, deterministic framework that had yet to be discovered. In contrast, Bohr and others accepted quantum randomness as a fundamental feature of nature, not a temporary gap in knowledge.

How Computers Generate Randomness

Despite being deterministic machines, computers need randomness for Monte Carlo simulations, games, cryptography, and machine learning. But how can a predictable device create unpredictability?

🔢 Common Techniques

Pseudo-Random Number Generators (PRNGs): Algorithms that use a seed value to produce a sequence of numbers that appear random. (e.g., Mersenne Twister)

Cryptographically Secure PRNGs (CSPRNGs): Stronger algorithms used for secure applications like password generation and encryption.

True Random Number Generators (TRNGs): Hardware-based, relying on physical processes like thermal noise or radioactive decay.

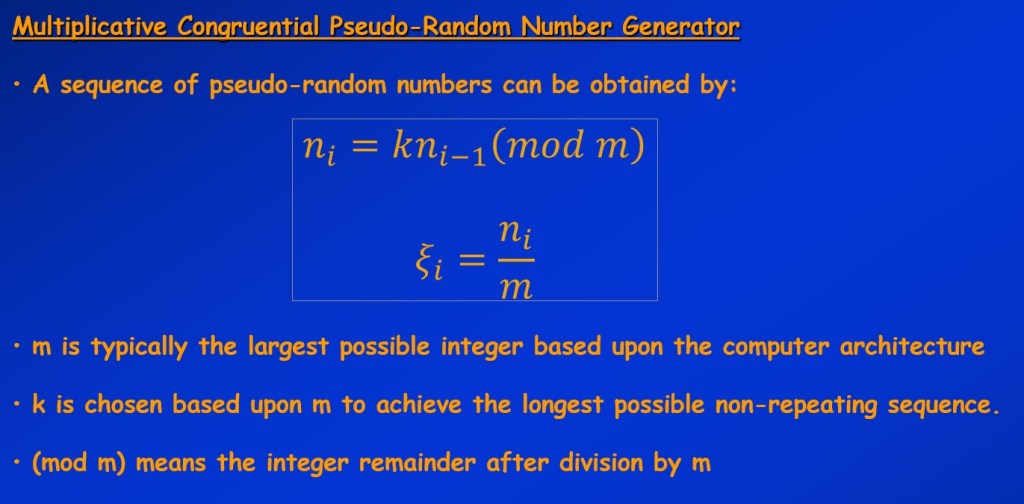

🔢 Multiplicative Congruential Generator (MCG)

An example of a pseudo-random number generator is the multiplicative congruential PRNG. MCGs are best suited for educational use, lightweight applications, or when simplicity outweighs the need for high-quality randomness.

Connecting Randomness to Monte Carlo Sampling

Monte Carlo methods are a class of computational algorithms that use random sampling to obtain numerical results. They are especially useful for solving problems that are deterministic in principle but complex in practice — such as integrating high-dimensional functions, simulating physical processes, or estimating probabilities. Instead of solving equations deterministically, Monte Carlo approximates results by simulating thousands or millions of trials and averaging the outcomes.

At the heart of Monte Carlo techniques is the generation of random numbers, which are used to simulate variables with known probability distributions. These methods rely heavily on pseudo-random number generators (PRNGs), making them a direct application of the randomness tools described earlier.

- Weather Prediction: Meteorologists use Monte Carlo-style ensemble forecasting to run many simulations with slightly different initial conditions, capturing the uncertainty and chaotic nature of weather systems.

- Finance: Monte Carlo simulations help forecast asset prices, model risk, and calculate the expected value of complex derivatives. Random price paths are generated using stochastic models like geometric Brownian motion.

- Radiation Transport: In medical physics and nuclear engineering, Monte Carlo methods simulate how photons, electrons, or neutrons interact with matter. Each particle’s path and interaction are randomly sampled, based on physical probability distributions.

Sampling Random Points in a Unit Square

One classic example that highlights Monte Carlo sampling and randomness is estimating the value of π by sampling random points inside a unit square and counting how many fall inside the inscribed unit circle. Because the area of the circle is πr² and r = 1, the ratio of sampled points inside the circle to total sampled points inside of the unit square approximates π/4. Multiply by 4 to estimate π.

Final Thoughts

Randomness isn’t just a quirk of probability theory — it’s an essential part of how our universe operates. From quantum mechanics to genetic diversity, from weather systems to digital encryption, randomness is part of our day-to-day operating system and a source of insight. With tools like Monte Carlo simulations, we can harness this unpredictability to solve problems, model complex systems, and even estimate fundamental constants like π.

Whether you’re a physicist, a coder, a biologist, or just a curious thinker — exploring randomness is a great way to embrace the beauty of uncertainty.

So the next time something random happens, consider this: perhaps randomness isn’t chaos at all, but a doorway to discovery.

This post includes content generated in collaboration with ChatGPT (OpenAI, July 2025).

Further Reading and References

Radioactive Decay

- Krane, K. S. Introductory Nuclear Physics. Wiley, 1987.

- NIST Radioactivity: https://www.nist.gov/pml/radioactivity

Genetic Mutations

- Griffiths, A. J. F., et al. An Introduction to Genetic Analysis. W.H. Freeman, 2020.

- NIH: https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/understanding/mutationsanddisorders/genemutation/

Weather and the Butterfly Effect

- Lorenz, E. N. The Essence of Chaos. University of Washington Press, 1993.

- NOAA Weather Education: https://www.noaa.gov/education/resource-collections/weather-atmosphere

Brownian Motion

- Einstein, A. Investigations on the Theory of the Brownian Movement. Dover, 1956.

- Feynman, R. P. The Feynman Lectures on Physics, Vol. 1, Chapter 41.

Tree Growth and Leaf Patterns

- Niklas, K. J. Plant Biomechanics. University of Chicago Press, 1992.

- Prusinkiewicz, P., & Lindenmayer, A. The Algorithmic Beauty of Plants. Springer, 1990.

Cosmic Ray Impacts

- NASA Cosmic Ray Resources: https://helios.gsfc.nasa.gov/cosmic.html

- Bazilevskaya, G. A., et al. Space Science Reviews, 137(1–4), 2008.

Animal Movement

- Viswanathan, G. M., et al. Nature, 381 (1996): 413–415.

- Bartumeus, F., et al. Ecology, 86(11), 2005.

Monte Carlo Sampling

- Metropolis, N., & Ulam, S. The Monte Carlo Method. JASA, 1949.

- Kalos, M. H., & Whitlock, P. A. Monte Carlo Methods. Wiley-VCH, 2008

Leave a comment