Introduction and Motivation

Religion is a daily reality that shapes calendars, communities, and conflicts. In my own life, I have friends and family for whom Catholicism is a non-negotiable guidepost—Sunday Mass, holy days, and parish rhythms—alongside other friends for whom religion is anathema. In the United States, we see the expanding footprint of the “Christian Right”, a reference to networks of (mostly) conservative Protestant evangelicals and allied Catholics who organize for public policy goals tied to pro-life advocacy, religious-liberty protections, traditional views of marriage/sex/gender, and parental control in education. It is not synonymous with all Christians, and many Christians reject its agenda. In the Middle East, the Israeli–Palestinian war reminds us how religious identity intersects—often painfully—with history, nationalism, and land claims among Jews and Muslims. Kashmir, a disputed region between India and Pakistan sits at the intersection of national identity and religion. The Kashmir Valley is overwhelmingly Muslim (≈96% per 2011 data), Jammu is majority Hindu, and Ladakh combines a Buddhist-majority Leh with Shia-majority Kargil.

The motivation for this post? To offer a concise and objective review of what religion is—paired with international and U.S. demographics—and to reflect on how our evolution as Homo sapiens is inseparable from the evolution of our spiritual and religious imagination.

A working definition

Religion is a shared system of meaning that relates people to what they regard as ultimate—through beliefs, rituals, experiences, ethics, stories, communities, and institutions. It explains the world, orients life, binds people together, and marks what’s sacred.

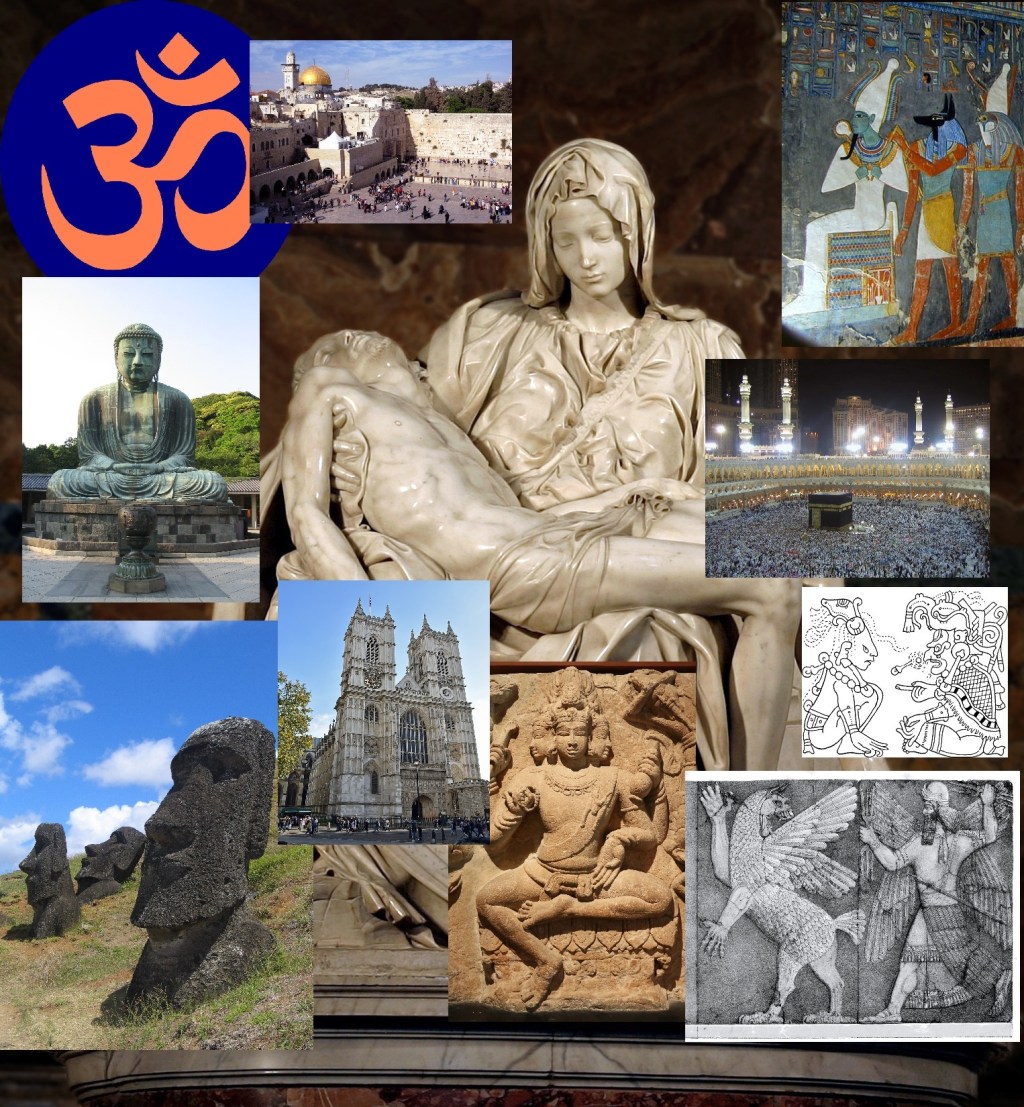

The Temple Mount: Site of the First Temple (traditionally Solomon’s, destroyed 586 BCE) and the Second Temple (516 BCE; greatly expanded by Herod the Great c. 20 BCE; destroyed by Rome in 70 CE). It is the holiest place in Judaism.

For muslims, it is known as al-Ḥaram al-Sharīf (“the Noble Sanctuary”), it houses the Dome of the Rock (completed 691 CE) over the Foundation Stone and the al-Aqsa Mosque (early 8th century). It is the third holiest site in Islam, associated with the Prophet Muhammad’s Night Journey (Isrāʾ and Miʿrāj).

Religion is a communal way of living in relation to what people hold as ultimate, expressed in shared beliefs, rituals, stories, ethics, and institutions that shape both personal identity and public life.

The Kamakura Buddha (Kamakura Daibutsu) is a monumental outdoor bronze statue of Amida (Amitābha) Buddha at Kōtoku-in temple in Kamakura, Japan. It’s a nationally designated treasure and one of the most recognizable icons of Japanese Buddhism.

Why it’s hard to define

Different cultures emphasize different pieces (ritual vs. belief, community vs. creed), and some traditions lack a single word equivalent to “religion.” Scholars describe it from a few angles:

- Substantive lens (what it is): Orientation to a transcendent or ultimate reality (God, gods, Dharma, the Dao, Nirvana).

- Functional lens (what it does): Creates belonging and moral order; offers meaning, identity, and coping with suffering.

- Structural/phenomenological lens (how it shows up): Recurring patterns—rituals, myths, symbols, ethics, leadership, sacred times/places.

Brahma is the creator god in many Hindu traditions, one of the Trimūrti alongside Viṣṇu (preserver) and Śiva (transformer/destroyer).

A handy checklist (Ninian Smart’s 7 dimensions)

- Ritual/practice (worship, prayer, sacraments)

- Experiential (conversion, awe, mysticism)

- Narrative/mythic (sacred stories)

- Doctrinal/philosophical (teachings, theology)

- Ethical/legal (moral codes, halakha/canon law)

- Social/institutional (churches, sanghas, ummah)

- Material (art, music, architecture, relics)

Ninian Smart (1927–2001) was a pioneering scholar of religious studies who helped establish the modern, secular, comparative study of religion in universities. He founded the first UK department of Religious Studies at Lancaster University (1967) and later became the first J.F. Rowny Professor of Comparative Religions at UC Santa Barbara (from 1976).

UC Academic Senate In Memorium

Michelangelo’s Pietà (1498–1499): Pietà (Italian for “pity” or “compassion”) depicts the Virgin Mary holding the dead body of Jesus after the Crucifixion. It’s a visual meditation on sorrow, love, and redemption—Mary’s intimate grief set against the hope Christians place in Christ’s death and resurrection.

Religion vs. spirituality

- Religion: communal, organized, tradition-shaped (structures, rites, authority).

- Spirituality: personal orientation to meaning/transcendence; may be inside or outside a religion.

The world’s religious composition (2020), using the latest comprehensive estimates from Pew Research Center.

| Religion | Estimated adherents (2020) | Share of world population (2020) |

|---|---|---|

| Christians | 2.269 billion | 28.8% |

| Muslims | 2.023 billion | 25.6% |

| Religiously unaffiliated (“nones”) | 1.905 billion | 24.2% |

| Hindus | 1.178 billion | 14.9% |

| Buddhists | 324 million | 4.1% |

| Other religions* | 172 million | 2.2% |

| Jews | 14.8 million | 0.2% |

| World total | 7.886 billion | 100% |

*“Other religions” includes Baha’is, Daoists, Jains, Sikhs, Shintoists, various folk/traditional religions, and many smaller groups.

Source: Pew Research Center’s 2025 report on global religious change (measuring composition in 2020). Figures may not sum perfectly due to rounding.

The current U.S. religious composition using Pew’s 2023–24 Religious Landscape Study (released Feb 26, 2025). Figures are rounded and sum to ~100%

| Group | Share of U.S. adults |

|---|---|

| Christian (total) | 62% |

| • Protestant | 40% |

| • Catholic | 19% |

| • Other Christians (e.g., Orthodox, LDS, Jehovah’s Witnesses, etc.) | 3% |

| Religiously unaffiliated (total) | 29% |

| • Atheist | 5% |

| • Agnostic | 6% |

| • “Nothing in particular” | 19% |

| Non-Christian religions (total) | 7% |

| • Jewish | 2% |

| • Muslim | 1% |

| • Buddhist | 1% |

| • Hindu | 1% |

| • Other (Sikh, Baha’i, Jain, etc.) | ~2% |

Source: Pew Research Center, 2023–24 Religious Landscape Study (published Feb 26, 2025)

Early signposts of religion or religious practice from archaeology/anthropology

- Intentional burials (early Homo sapiens):

Qafzeh/Skhul, Israel—Middle Paleolithic burials with grave goods/ochre; among the oldest H. sapiens interments. Recent finds at Tinshemet Cave (~100,000 years) reinforce patterned, deliberate burial in the region. - Neanderthal burials (debated “flower burial”):

Shanidar Cave, Iraq—Multiple Neanderthal interments (~55–45k years); new work refines dates/context and revisits the famous “flower burial” claim. - Personal ornaments & abstract symbols:

Blombos Cave, South Africa—Engraved ochre (≥75–100k years) and shell beads; a 73k-year ochre drawing is among the oldest known abstract designs, pointing to symbolic behavior. - Therianthropic/figurative cult images:

Lion-man of Hohlenstein-Stadel, Germany (~40k years)—mammoth-ivory human-animal figure, often linked to myth/ritual imagination. - Paleolithic cave sanctuaries:

Chauvet Cave, France—Aurignacian paintings (c. 36.5–30k years); UNESCO calls them the earliest known pictorial drawings—likely tied to ritual narratives. - Elaborate Upper Paleolithic burials:

Sunghir, Russia (~34k years)—lavish interments with thousands of ivory beads and ochre; strong signals of ceremonial status and belief. - “Venus” (female) figurines:

Venus of Hohle Fels, Germany (42–40k years)—oldest undisputed human depiction; often interpreted within fertility/ritual frameworks. - Pre-Pottery Neolithic ritual megaliths:

Göbekli Tepe, Türkiye (c. 9600–8200 BCE)—T-pillar enclosures with carved fauna; UNESCO notes likely ritual/funerary functions among early sedentary groups. - Neolithic house-shrines & bucrania:

Çatalhöyük, Türkiye (c. 7500–5700 BCE)—rooms with plastered bull skulls (bucrania) and installation art suggest domestic cult/shrine activity. - Megalithic solar alignments:

Stonehenge, England (c. 2500 BCE) aligned to solstices; Newgrange, Ireland (c. 3200 BCE) channels winter-solstice sunrise into its passage tomb—clear cosmological/ritual design. - Human–animal ritual burials (dogs):

Natufian Levant (~12k years)—dog interments with humans indicate symbolic ties beyond subsistence (early domestication with ritual overtones). - Homo naledi burials (~250k years, South Africa): New eLife papers argue deliberate interment; other scholars dispute the claim—an active, high-profile debate.

Caveat: “Religious” is an interpretive label. Archaeologists infer ritual from patterned burials, symbolism, monumentality, and celestial alignments; exact belief systems remain unknowable.

Of the religions practiced today, what is considered the oldest?

Hinduism is most often called the oldest continuously practiced major religion. Its roots go back at least 3,000–3,500 years to the Vedic tradition (Rig Veda often dated to ~1500–1200 BCE), with possible precursors in the Indus Valley.

- Zoroastrianism: Very ancient too; the Gathas (hymns of Zarathustra) may date to ~1200–1000 BCE (some scholars place them later).

- Judaism: Emerges from Iron Age Israelite religion; continuous practice traceable by texts/inscriptions from roughly 1st millennium BCE.

- Jainism: Historically evident with Mahavira (~6th c. BCE), though the tradition claims far older, pre-Vedic origins.

- Indigenous traditions (e.g., Australian Aboriginal religions) are extraordinarily ancient in cultural continuity, but they aren’t always classified the same way as “world religions.”

So, if you mean the oldest major world religion still widely practiced, the conventional scholarly pick is Hinduism; if you broaden to ancient, continuous religious cultures, the picture includes Zoroastrianism, Judaism, Jainism, and very long-lived indigenous traditions as well.

Leave a comment